By Whitney Richards-Calathes

Every few months I have the same dream. I am in a room. Or is it hallway? A bedroom? Maybe standing in front of a desk. There can be a wall with pictures hung up. The scenes change, but they are always the internal rooms of a home. And then, in those familiar rooms we all know, I explode. Always, on repeat, each dream. Arms wild, tearing apart books; I fling a desk across the room; I scratch at the walls until nothing is left. Piles of mess lay at my feet, familiarity broken apart, destroyed. I am undone, upended, roaring, screaming, hot emotion pouring out my throat from an endless deep, deep pool inside of me. It’s rage. Nothing but an uncontrollable and immense rage.

I wake up, heart racing. Take a drink of water to cool it down, to coax it back in. Back to sleep.

********

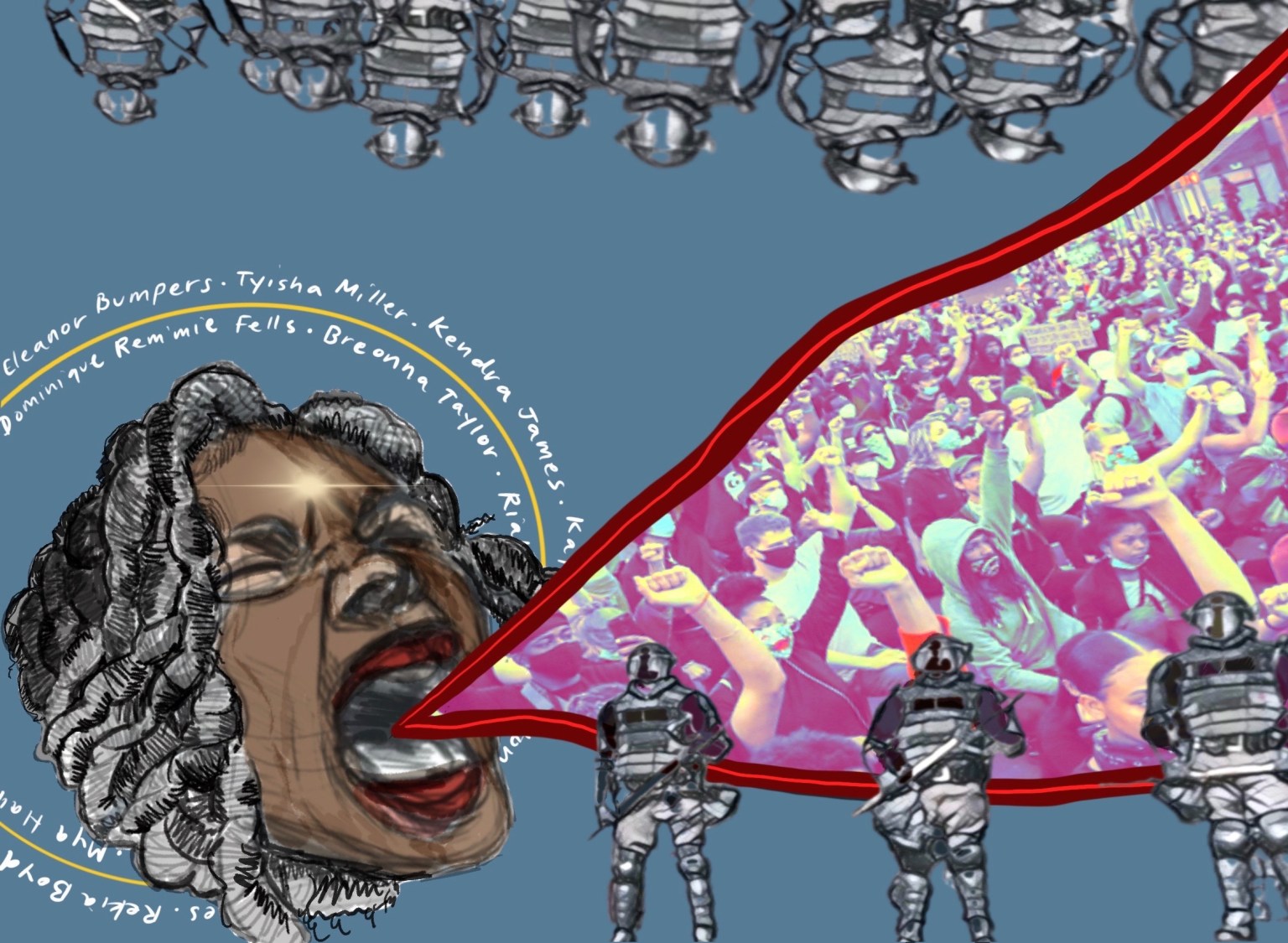

Since the end of May, we’ve seen protests surge across the United States and the globe. All in response to the killings of Black people at the hands of police. Bodies take to the streets calling out anti-Blackness and state-violence. Crowds gather to scream out – #BlackLivesMatter. And we see a version of my dream too. The surging screams, the roar from bellies, and on some nights, windows broken, flames alive, furniture and clothes and books upturned. Protest is rage embodied: stomping feet, pain, and grief wrapped up and catapulted towards a belief in something better. More just. More free.

I am a Black woman from the Bronx, so I am no stranger to rage or to fires. Let me be more accurate. I am a Black woman from the Bronx that believes in nothing less than a Black feminist version of abolition. Rage, fires, destruction and new worlds are some of my closest companions.

But, as I hear friends back from being in the streets, saying “I didn’t see anyone that looked like me,” coupled with thought pieces on Antifa, pictures of white boys in gas masks, and the dearth of rallying around Black trans and cis women’s deaths, I’m thinking to myself: In this moment, who does rage belong to?

There are Black women in the streets.

Long term organizing by Movement For Black Lives, Black Lives Matter, andBYP100 all center Black femme leadership, vision, and labor. Powerful speeches by Tamika Mallory and Kimberly Latrice Jones break down the necessity of the rage behind looting and protesting. #BlackLivesMatter founders, Patrisse Cullors, Opal Tometi, and Alicia Garza – all Black women – provide daily updates to the public in the form of sharp analyses and calls for justice for the families that have lost loved ones. My sisters and I discuss over Zoom what to write on posters and signs for large mobilizations occurring in our respective cities.

So, I am not erasing Black women’s bodies or our longstanding efforts towards liberation. The foundational work of organizing, base building, and grassroots mobilizations – the work of strategic abolition – is undoubtedly Black and feminine of center. And yet, something doesn’t feel quite right. There’s the silence on the killings of Black trans women. And the framing of the moment as solely a response to the murder of George Floyd. George Floyd is the center point of Dave Chapelle’s comedic set “8:46”, which gathered over 16 million views in a matter of days. In it Chapelle talks about the pain, the hurt, and the rage of being a Black man watching cops on kneel on Floyd’s neck. When Chapelle speaks, we feel the heavy weight of emotion that sits at the back of his throat because for many of us, that feeling also lives in our bodies. And still, we get to the end of his almost thirty minutes without one mention ofBreonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Charleena Lyles. A legitimate moment of release for a Black man in the public eye, but why didn’t he bring us, Black women, along with him?

As a Black feminist that believes in abolition I try to uplift the names of Black femmes killed by the state alongside those of Black men. Organizations within the movement towards abolition do the same. Campaigns like #SayHerName grew to call critical attention to the deadly coalition of heteropatriarchy, anti-Blackness, and state violence. But where do Black women exist in this moment beyond our labor? Beyond our capacity for networking, for holding space, our ability to stand alongside, and our behind-the-scenes work? How are we valued not just as the ones that “hold it down,” but also as complex, feeling, nuanced, hurting people? Where are the platforms, the filmed segments, the news pieces capturing, collectively witnessing and, dare I imagine, collectively understanding our upset? Our messy pain? Our ocean-deep anger, exasperation, and fury? Do people see that we are upset? Can others feel our rage? Are we even allowed to feel our rage?

Rage is a critical ingredient to social transformation. A catalyst that can destroy, uncover, and reveal. We are all entitled to it, especially those that survive centuries of oppression. It can be sharpened and honed. Just like any well-pointed instrument, it holds the possibility of piercing through. Rage is a tool for our movement. And abolition requires of us a particular type of rage; a level of indignation so great that we must tear a whole thing down to its very bits and build anew.

What is erased in our efforts for abolition when there’s no space for Black women’s rage?

When there’s no space for Black women’s rage, we erase all their names: Eleanor Bumpers. Alberta Spruill. Shantel Davis. Shelly Frey. Kayla Moore. Kyam Livingston. Miriam Carey. Michelle Cusseaux. Tanisha Anderson.Rekia Boyd. Aiyana Stanley-Jones. Pearlie Golden. Mya Hall. Korryn Gaines. Atatiana Jefferson. Pamela Turner.Michelle Shirley. Ralkina Jones. Dominique “Rem’mie” Fells. Riah Milton. Deborah Danner. Alexia Christian. Priscilla Slater. These are only a small few. Why are we not raging at all this death? At all the extinguishing of this Black femme life?

When there’s no space for Black women’s rage, we erase and diminish Black women’s feelings.

Black women’s rage is often leveraged to incarcerate, police, and punish us. Our anger gets us called Sapphire. Our cultural expressions get labeled as “attitudes,” “bad behavior,” and “ghetto.” We get expelled, our motherhood surveilled, and our voices quelled. And when our emotions get ignored, we are seen as incapable of feeling pain and get called Superwomen while quietly suffering the physical and emotional consequences. Black women do not get permission to live our full emotional spectrum and the texture of our lives without dire, often punitive consequences. Understanding ideologies and practices of punishment require us to give and create space to Black women’s feelings. Abolition isn’t just ideological, it’s emotive and somatic.

When there’s no space for Black women’s rage, we erase even more of what is made invisible.

Over ten years ago a teenage Black girl in Chicago told me about the time a male officer publicly stripped searched her and her sister on a winter afternoon. When she spoke back in anger to him, he hit her across the face and said, “You too pretty to have a mouth like that on you.” Eight years ago, on a summer day in Brooklyn, my friends and I walked past a group of officers and when we didn’t answer their catcalls, one in blue whispered in my ear, “Just wait until I get you in handcuffs … the pink furry kind.” Sitting on her living room couch in Los Angeles three years ago, a twentysomething Black woman remembered the time a cop stopped her and her friends. He slipped his hand up her skirt and touched. She was fifteen at the time. These incidents, all at the hands of police, never got recorded. They do not end in arrests. There is no report put on a desk. They never get to be a tick in our tallies towards the proof of our own oppression. They are embodied, real, and alive experiences made invisible. If we do not allow the rage in Chicago, Los Angeles, and Brooklyn to come to the surface, what does our abolition do for these stories?

Listening to Black women’s rage is more than equity. It is a necessity for abolition. Through our experiences, our pain, and our messiness, we arrive at a more full and clearer picture of what needs to get burned down. I do not want an abolitionist practice that only relies on Black women’s labor. Nor should you. Black women are whole, complex, full, and gorgeous people. Letting us live, and demanding that we get to live, requires a space for us to do that fully.

So, what does a righteously rageful Black women’s abolition look like?

Saying the names of Black cis and trans women that have been killed at the hands of law enforcement. All the time. Everyday. Everywhere.

Stepping in to hold the unglamorous movement work (e.g. phone banking, childcare, cooking, organizing marches, printing fliers, editing, cleaning, etc.) so Black women can feel, live, cry, grieve, recover, and be angry.

Putting Black women and femmes in positions of power within organizations that do abolition work. We do not need more white executive directors working in Black communities.

Understanding the links between heteropatriarchy, anti-Blackness, and punishment.

Donating to causes, campaigns, organizations, and platforms that address violence against Black trans women and that are led by Black trans women.

Stopping gender-based violence. This includes being honest about the gender-based violence that occurs in abolitionist spaces. Because someone is an activist does not mean they do not sexually harass, rape, gaslight, or hurt femmes. And please, let’s stop venerating dusty movement leaders that we all quietly know hurt and prey on women and femmes in the work.

Defining organizing beyond performative social media posting, protesting and long all-night work shifts “for the movement.” Create and demand that involvement is accessible for mothers, caretakers, and laborers (most essential workers were Black women). See everyday Black women beyond the nonprofit scene as powerful, insightful, and visionary.

Uplifting historic and contemporary Black women abolitionists: Nanny of the Maroons, Janetta Louise Johnson, Maria Firmina dos Reis, Je’Kendria Trahan, Mary Hooks, Deshonay Dozier, Maria W. Stewart, Asha Ransby-Sporn.

Supporting all forms of Black femme leadership (e.g. working class, young mothers, genderqueer, trans women, undocumented Black femmes).

Demanding policies that go beyond defunding the police, and that instead, abolish all of our addictions to punishment (see the previous line about heteropatriarchy and anti-Blackness).

Connecting our abolition work to movements for freedom across the Global South and the African Diaspora, because intersectionality is a gateway towards liberation.

Listening to Black women’s anger instead of trying to quell it (or call the police on it).

Celebrating our rage, learning from it, empathizing with it, and feeling it alongside us.

Abolition is not only about the institutions of policing. It is about the roots of violence and oppression. Abolition helps us fight for a radically new world, with new values and systems of relating. We are all addicted to punishment and the histories of misogynoir that feed it, so we all need an abolitionist practice. Therefore, my call is not simply for those that are waking up and radicalizing in this moment – it’s for those of us that have been seeing the fires for a long time, that have lived through many burn cycles, those of us that know the surge of adrenaline that comes from chanting in a crowd of 10,000. I ask you: what have you done for Black women? And what space do you actively create to learn from our leadership and our rage?

Maybe next time, when I dream a dream of destruction, I will wake up and sip my water not to extinguish, but to hydrate, to fill up, and to re-energize myself for the battles ahead. My fire has no intention of stopping. My rage is here to stay.

********

Whitney Richards-Calathes (she/her) is a community-based researcher and transformative justice practitioner. She collaborates with grassroots organizations and institutions to do participatory research and youth leadership development. Her work is in service to abolitionist movements. She holds a PhD from The Graduate Center and writes about the impact of incarceration on generations of Black women. Her work is based in NYC and Los Angeles. She is from the Bronx. Find her on instagram @call.me.shaney and Twitter @whitneyinpublic