In 1972 the national Housing Finance Act (HFA) raised the rents of council houses. There was national opposition, particularly strong in Liverpool, where in September twenty tenants’ associations agreed to withhold rents. The strike spread through existing tenants’ associations, “Fair Rents” Action Committees and mass meetings. They were supported by a new alternative media including the Scottie Press, Liverpool Free News and, in particular, Big Flame. Tenants also burnt rent bills, organised protests and disrupted council meetings. By October rent strikes had broken out in Birkenhead, Bootle, Cantril Farm, Huyton, Everton-Scotland Road, St. Helens and Warrington. These strikes were partial rather than total, just withholding the increase in rent.

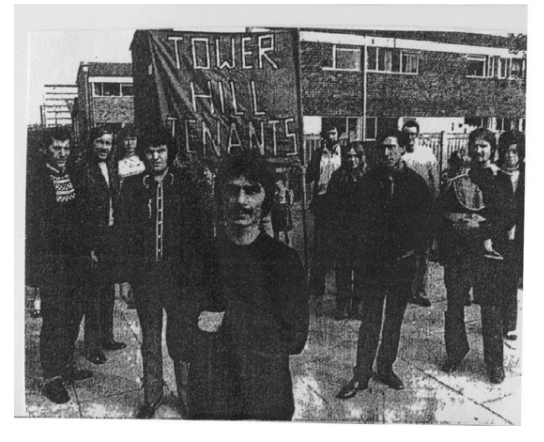

The response was different in Kirkby, where a number of tenants had been involved in the 1969 Abercromby Rent Strike. In Tower Hills a mass meeting of 450 tenants agreed to a total rent strike, forming a group called THURAG with representatives for each street and block. In October, 1,475 Kirkby tenants withheld their rent completely. The “Over the Bridge” group, one of eight associations in Scotland Road, was alone in joining Kirkby, with almost complete support from their 570 residents. The total rent strikers proved far more resilient than their counterparts, and by March 1973 were effectively alone.

From the get-go housewives and the unemployed formed flying pickets in Kirkby to “follow” rent collectors. Both Tower Hills and “Over the Bridge” quickly became no-go areas for bailiffs. On November 10th over 900 tenants resisted an eviction in Tower Hills. 50 tenants surrounded their home, while the rest sealed off the estate to all traffic. When THURAG’s spokesperson was threatened with an eviction, 400 tenants travelled from “Over the Bridge” to defend him. Preparations were made with a telephone tree setup to sound WW2 sirens, an assembly point and volunteer patrols. Community spirit flourished with a tenants community centre, weekly newsletter and an estate-wide party on the night of the strike’s anniversary.

By June 1973, despite its small size, Kirkby council had the third highest rent arrears in the country. By October, Tower Hills managed to spread the strike to the Northwood estate and Croxteth, despite the fact that at this point rent strike was clearly in remission. They ignored court summons and decided to continue fighting their “own way.” On December 6th, two strikers were arrested in their homes for contempt of court and taken to Walton Jail, where they received a warm welcome from the inmates. Within a few hours roadblocks were set up around the town and four industrial strikes broke out. That evening tenants from across Merseyside picketed the jail, while the frightened authorities stockpiled anti-riot gear. On the 21st, with five more arrested, Tower Hills agreed to end the strike by majority vote in exchange for “no more legal action.” On the same day the strike ended in Oldham, followed by the remnants of the strike in Liverpool, Merseyside and Sheffield within a month.

Unlike the successes of the 1968 and 1969 rent strikes, the 1972 strike ended after its last bastion fell with no material gains. While it’s not worth overstating its failure, after all they only had to repay the rent and prisoners were released, it is worth reflecting on why the strike failed.

Promises from local Labour councils to refuse to implement the HFA came to nothing, meanwhile they urged non-payment and issued eviction notices. Due to faith in the Labour Party many tenants’ associations, including the only real national association, were surprised when these promises didn’t materialise and so were slow to respond. The overwhelming majority of associations also opted for partial strikes, which are less disruptive, yet appear more legitimate and “fair” to their masters. In contrast, THURAG and “Over the Bridge” underwent a process of radicalisation and rejected Labour and the legitimacy of the state. It took 14 months until Tower Hills strikers were arrested – just imagine the state’s reluctance if militant resistance had spread beyond Merseyside. Since the HFA was a national policy the tenants required a strong national response, but this never really got off the ground and where it did it pulled its punches.

On the other hand, there was not enough industrial resistance to the HFA. Unlike tenants, workers have the capacity to swiftly shut down the economy. Nationally there was no real opposition from the unions. Locally there was industrial support for the rent strike at the beginning from Ford’s and Bird’s Eye workers, but both suffered layoffs due to their actions. Luckily all those workers were re-hired, with mothers from THURAG joining their picket lines for reinstatement. The arrests that broke Tower Hills happened a few days before the last payday prior to Christmas, in an attempt to undermine any industrial response. Despite strong support from the rank-and-file, the union hierarchy were also reluctant, failing to call meetings or refusing to support Tower Hills at the end due to technicalities.

It is possible to win national gains as tenants. The Poll Tax rebellion built a successful national movement for non-payment, while the 1915 Glasgow Rent Strike saw strong industrial support for tenants and won a national rent freeze.