Post written by Watch the Channel and Calais Migrant Solidarity

24/11

As news began circulating that a boat had sunk in the middle of the Channel and that 27 people, men, women and children, had lost their lives on Wednesday 24 November, both the British and French governments were quick to blame ‘people smugglers’ for the loss of life. The information that has emerged since shows that it was the decision on the part of authorities not to intervene, nor cooperate with one another, after being alerted to the boat in distress that lead directly to their deaths.

One of the two survivors, Mohammad Khaled, spoke with Kurdish news network Rudaw and explained his story. He says the travellers got onto the boat and entered the water close to Dunkirk at around 21:00 CET on Tuesday night. Three hours later they believed they had arrived at the dividing line between British and French waters.

Mohammad says that during their crossing the right sponson was losing air and waves were coming into the boat. People were bailing out the sea water and using a hand pump to reinflate the right sponson as best they could, but after the pump stopped working they called to the French coastguard for rescue. They shared their GPS position via a smartphone with the French authorities, to which the French responded that the boat was in British waters and that they had to call the British. The travellers then called the UK Coastguard who told them to call back to the French. According to his testimony “Two people were calling – one was calling France and the other was calling Britain”. Mohammad recounted that: “The British police didn’t help us and the French police said, “You’re in British waters, we can’t come.” Despite both HM Coastguard Dover and French Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre at Gris-Nez knowing the location and condition of the boat, neither launched a search and rescue operation.

A relative of one of the people on board, also interviewed by Rudaw, explains that the problems with the sponson began around 01:30 in the morning GMT. He was in contact with the people on board up until 02:40 GMT and was also monitoring the boat’s position, shared live on Facebook. He insists that at this time the boat was in British waters and that HM Coastguard was aware of the situation. He states: “I believe they were five kilometers inside British waters,” and when asked if the British were aware of the boat in distress he replied: “100 per cent, 100 percent and they [British police] even said they would come [to the rescue].”

The British denied that the boat was in their waters when asked by Rudaw. A statement from the Home Office reads: “Officials here confirmed last night that the incident happened well inside French Territorial Waters, so they led on the rescue effort, but [we] deployed a helicopter in support of the search and rescue mission as soon as we were alerted.” However, Rudaw (as of 29/11) still has not received a detailed response on whether or not HM Coastguard had received a distress call from the vessel during the night or early morning.

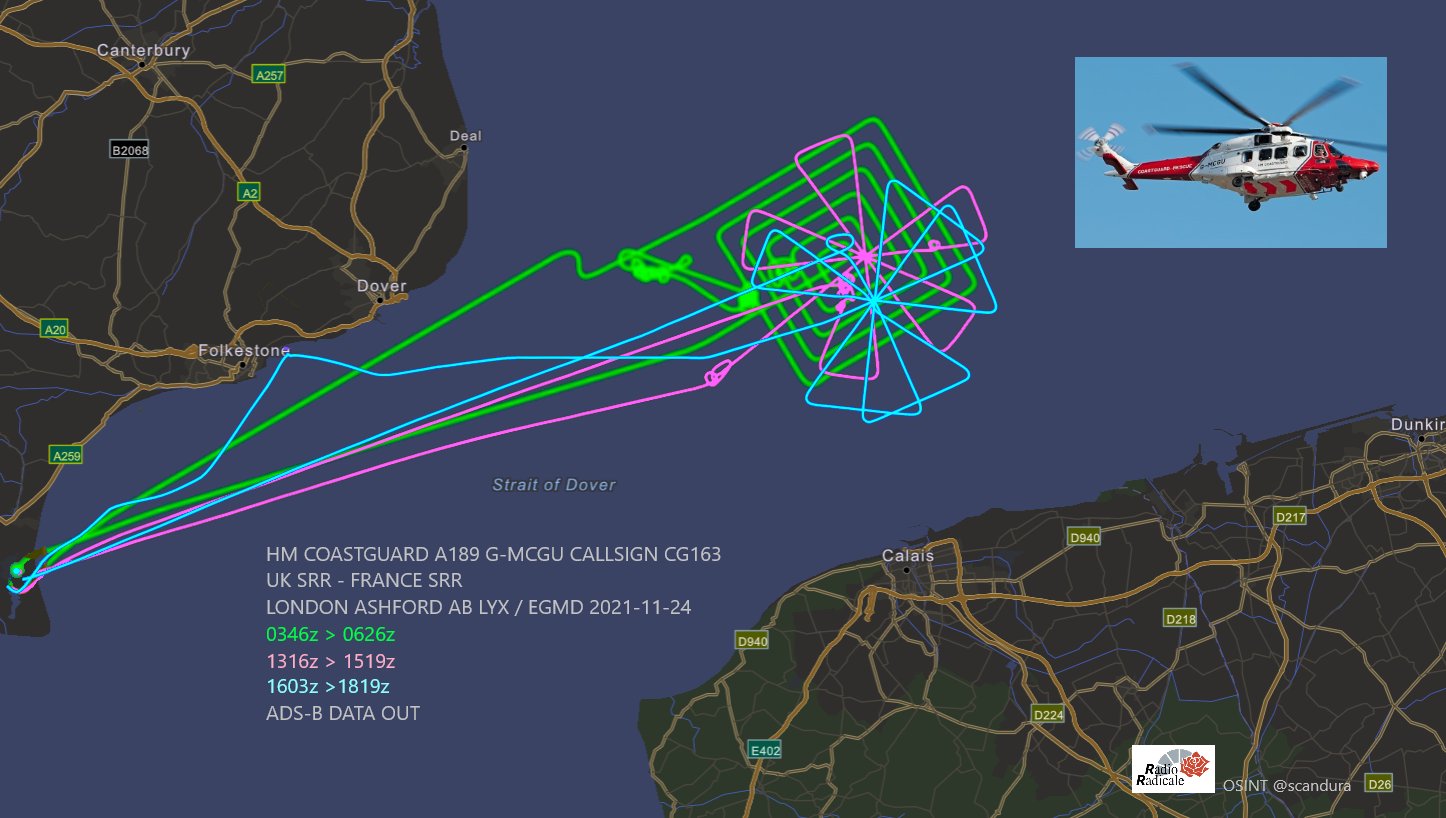

One question looming over the Home Office’s statement is what time-frame does it consider constitutes ‘the incident’? The statement mentions deploying a helicopter “as soon as we were alerted”. Flight tracking of HM Coastguard’s helicopter G-MCGU (named “Sar 111232535” on MarineTraffic) by Sergio Scandura shows that it did three flights over the area on 24 November:

The first time was between 03:46 and 06:26 GMT where it appears to fly an “expanding square” search pattern, and the circle some specific targets that it finds. If this is the launch “as soon as we were alerted” the Home Office refer to, did this helicopter spot Mohammad’s boat and were there other vessels launched to assist in the search and rescue mission?

The next time the helicopter was launched was in the afternoon, at 13:16 GMT. It appears to do “sector search” and again circle some specific locations. This is around the time that the French launched their search and rescue operation, and is more likely the launch and “incident” referred to in the Home Office’s statement. Only at 15:47 did the Préfecture maritime Manche et mer du Nord first Tweet that they were coordinating a search and rescue operation involving a shipwreck in the Channel. Data from MarineTraffic show that boats involved in the rescue, for example the Notre Dame Du Risban lifeboat of the SNSM only began to move towards that location around 14:00, around 12 hours after Mohammad and his relative state that they first spoke with the authorities. Most of the activity of the French vessels tasked with the rescue operation involved takes place around 51°12′ N, 1°12 E, a position only about 1 mile East of the line separating French from British waters.

This means that for around 12 hours, between approximately 02:30 and 14:00, more than thirty people boat were left adrift in a boat that was sinking and without an engine in one the busiest and most surveilled shipping lanes in the world. More information is still needed to definitely prove that Mohammad and the others in his boat were in British waters, for how long, and that their distress situation was known to HM Coastguard. However, given the testimony of Mohammad the relatives of others in the boat, the first helicopter launch, and the amount of time which the boat was left to drift at sea, it is extremely likely that HM Coastguard was aware of the situation. But instead of intervening to save lives at sea, it appears they decided to play politics and hope that the travelers would drift back and drown in French waters.

Mohammad testified that even though water was entering the boat through the night and people were becoming submerged “Everyone could take it until sunrise, then when the light shone, no one could take it anymore and they gave up on life”. By the time the sun started to rise they has already lost hope of survival.

20/11

Mohammad Khaled’s account from the 24th is not the first of what appears to be deliberate non-assistance for migrant boats in distress in the Channel. Less that a week beforehand, on 20 November, we spoke with someone else whose calls for help in the Channel close to the border line seem to have been deliberately ignored by the British and who provided the following account of his journey:

It was at 3am on Saturday 20 November when we put the boat in the sea. We are 23 in the boat.

After three hours, I think, we reached the British border then the fuel ran out, I think at 7 o’clock, and then we decided to call the 999 [the British emergency number]. Then we called and they told us you are in the French water without asking us for our location. They told us to call 196.

First of all we did not agree to call the French. We were trying to paddle but it was very difficult because of the waves. Then we decided to call the French. When we called they asked us to send our live location, then they told us ‘You are in UK waters’.

Then we called the British again many times but they kept repeating that we were in French waters and then they ended the call. The UK guys answered us in a very rude way and it seemed like he was laughing at us.

I told him two times that there were people dying in here but he really didn’t give a shit. We sent our live location a second time to the French coastguard. We also called them again, we were trying to reach them by two phones but they kept telling us we were in the UK waters.

So I decided around 9.30am to call Utopia. Then they helped us and they were forcing the French authorities to send the boat to save us around 10am or 10.30am. The reason why I’m sharing this thing because I don’t want it to happen again because it’s related to people’s lives.

Utopia 56, after being called by the people in distress, called to CROSS Gris-Nez, the French Maritimate Rescue Coordination Centre responsible for the Straits of Dover. Utopia 56 relayed the information they received and the position of the boat, and were then told by the CROSS that they were sure that the British had deliberately not intervened and let the people drift back to French waters.

Deathly consequences of a failure to cooperate

These two cases indicate that although Border Force has yet to implement forcible push-backs, turning around migrants boats’ with jet skis or dragging them back into French waters, push-backs are already occurring in the form of HM Coastguard deliberately refusing to come to the aid of migrants which it believes will drift back into French waters. This deliberate non-assistance is a deadly tactic that leaves people out at sea, in overcrowded and unseaworthy vessels, for many hours after they call for help, to traumatise the travellers and deter them from attempting to make further attempts at crossing to the UK by boat.

The French and British Coastguards “have a duty to cooperate together to prevent loss of life at sea and ensure completion of a search and rescue mission” under the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea and the Search and Rescue Convention. This includes a responsibility on both sides to contact one another as soon as information is received about people in danger and to cooperate on search and rescue operations for anyone in distress at sea.

However, it appears that the UK’s current anti-migrant policies mean that this cooperation in fact does not exist for migrants in distress in the Channel. Especially the UK government does not want to be seen to rescue boats immediately after they enter their waters. Furthermore, their criticism of the French for (in their eyes) not doing enough to intercept migrants’ boats at sea or prevent them from departing from the French coast, has seemed to poison diplomatic and operational relationships between the countries. For example, the Journal du Dimanche recently published that even in the investigations of smuggling networks there has been a breakdown in French and British cooperation.

Instead of cooperating to save lives at sea the Franco-British response has been to argue with one another, introduce more border policing measures (including aerial surveillance from Frontex), blame the victims and continue to scapegoate the smugglers. This has been useful to detract from their own failings over recent days, but will not improve the situation for the people who actually have to undertake such journeys. Further securitisation of the beaches and seas will only push people to try longer, more dangerous routes where there may not be good telephone network coverage. Small boats in distress will find themselves further from the large number of potential search and rescue assets located in the Straits of Dover.

Deaths of their friends and hours in distress adrift at sea without rescue will not dissuade people from trying to make the same journeys as they have no other options. Suggested solutions such as humanitarian visas will not provide everyone who needs it with a safe route to the UK. Others will continue embarking in small and unseaworthy vessels. Simultaneously, millions of people make this same journey each year aboard the ferries and trains that criss-cross the Channel several times a day without incident. Only by according the right to freedom of movement to all will we end the border apartheid and prevent further lives from being lost at sea.