From: https://roarmag.org/magazine/everyday-borders-everyday-resistance/

In recent years there have been many instances of increased migrant mobility at Europe’s borders, such as the arrival of 30,000 migrants on the shores of the Canary Islands in 2006, the collective border jumps at the European enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in northern Africa, and, more recently, the arrival of over one million people on the Greek islands off the Turkish coast in 2015 and 2016. These are generally dubbed as “border crises”, evoking a sense of emergency, of a Europe “under threat”. However, these crises are systemic, they are products of the EU’s border politics and they signal moments of rupture in its seemingly orderly governance.

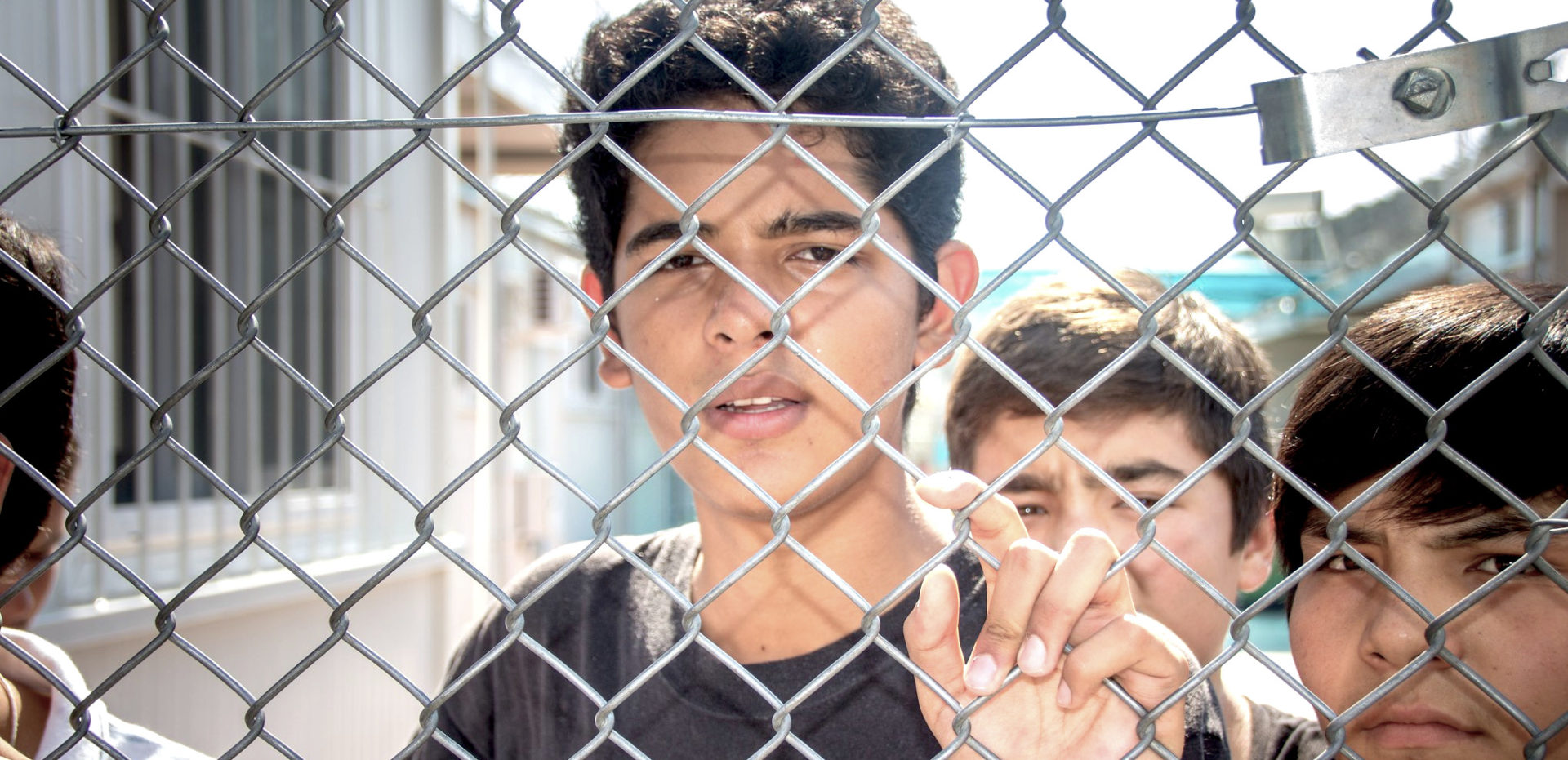

As a result, practices and spaces of confinement for migrants — hotspots, transit and reception centers, off-shore, extraterritorial, temporary and mobile detention facilities — proliferate and multiply. But the EU’s borders do not exist only at the border. They can equally be found in FRONTEX’s pre-frontier digital surveillance system, the Schengen Information System where the data of persons denied entry are kept, and the Eurodac database where fingerprints of asylum seekers and detained migrants are stored.

So the border is not really a place, a physical space outlining the territories of states. Borders are instruments of power that reproduce hierarchies of class, race and gender and they are enacted in our daily life and everyday spaces: at our workplaces, on the bus, in our squares, at the supermarket. This everyday border might be invisible to most, but it shapes the lives of those on the margins of our societies on a daily basis.

It is more useful to think of the border as a provisional arrangement, an assemblage of different practices, places, spaces, laws and regulations, policies, actors, politics, knowledges and experiences. All these different components come together and form the border regime, which, despite having significant spatial characteristics, is abstracted and diffuse.

In recent years, everyday manifestations of the EU’s border regime have intensified severely. Migrants find themselves confined and isolated in camps, forced to live under conditions that endanger their lives, physical and mental health, and future prospects. The COVID-19 pandemic, the lockdowns, travel restrictions, border closures and curfews have exposed the way that the border works to many more of us.

But, if borders materialize through everyday practices and play out in our daily lives, this opens up possibilities for their contestation through antagonistic practices of solidarity and care, as the response of the public has shown in the form of mutual aid networks, rent and labor strikes, and migrant solidarity initiatives. This is particularly consequential considering the increasingly shared vulnerability of both migrants and non-migrants. By focusing on everyday embodied practices of solidarity and on the collectivization of care on the basis of shared precarity and vulnerability between migrants and non-migrants, we can begin to dismantle the exclusions, segregation and oppression produced by the border.

Borders in the age of the pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdowns have disrupted various commonplace assumptions and misconceptions around mobility/immobility, border security, globalization, cosmopolitanism and the nation-state, revealing much deeper patterns and trends in border management.

One of the main measures to contain the spread of the virus have been travel bans and other restrictions of movement. By mid-March, most states restricted access to their territories only to citizens and permanent residents, deepening existing cleavages between citizens and non-citizens. These measures are far-reaching and unprecedented, but they build on past trends, expertise and technologies, and will have future implications for the governance of human mobility and the deterrence of unwanted migration.

For example, police checkpoints on our streets, in our neighborhoods and on highways, ports and toll stations, requiring people to prove their legal status and justify their movements, build on existing practices of border surveillance: it is everyday borderwork, but on steroids. What migrants have endured for decades on our streets through police checks and racial profiling is intensified and extended to include non-migrants. Such intensification of the surveillance of our bodies and movements will certainly leave a mark long after the crisis is normalized.

The pandemic has made it glaringly obvious that control over the movement of workers is one of the core functions of borders today. Migrant workers from Eastern Europe have been exempt from travel bans and are brought to Western Europe on chartered planes and buses to harvest crops: asparagus in Germany, strawberries in France, soft fruit in Scotland. In this process, they expose themselves to poor work and health conditions, dire living standards and an increased risk of infection. And all for a sub-minimal wage.

In Austria, care workers were flown in from Bulgaria, Croatia and Romania, despite hostile policies, such as a merit-based migration system and integration through achievement, introduced just two years ago. The UK extended the visas of over 3,000 migrant NHS workers, Germany recruited non-licensed medically trained migrants, while other states, such as Spain and France, relaxed migration rules for medically-trained asylum seekers and refugees. Such instrumental use of migrants will not lead to a re-evaluation of immigration policies and a curbing of xenophobia, as many hope today, but will instead widen the gap between who is perceived as “deserving” and who is not; between skilled and unskilled, valued workers and “fortune seekers.”

The contradictory and improvised enforcement of travel bans expose sustained socio-economic inequalities inside the EU and disrupt our assumptions that mobility is associated with privilege. They demonstrate clearly that we are not all equally affected by the pandemic, but rather that the impact of the public health measures varies depending on one’s class, race and gender.

This is not only true for the seasonal migrant workers mentioned above, but also for industrial workers in Italy and elsewhere made to work through the lockdown on cramped assembly lines; the communities of color in the US and the UK, who are disproportionately represented in COVID-19 deaths as a result of pre-existing socio-economic inequalities; and women who are expected to cover increased family care needs while also suffering disproportionately from rising unemployment, precariousness, impoverishment, and an increase in domestic and everyday violence.

All in all, it has become clearer than ever before that human mobility, governed through the border, is an instrument of power, bound-up in power hierarchies, often used punitively, and functioning in a gendered, raced and classed way. The state is currently mobilizing a whole new legal and technological arsenal to exert control over peoples’ movements through external, internal and biometric borders.

States deploy borders not so much to stop people from migrating, settling and working in new places, as to shape the conditions of their lives, the job opportunities and labor conditions available to them. In other words, borders define who can inhabit, where, for how long and with what rights.

The EU border regime governs migrant lives through criminalization and victimization, producing docile subjects. This happens during the everyday encounters migrants have with others, in which they must constantly prove, depending on class, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, race, age and physical ability, that they have the right to be there, to work, that they are entitled to health care and housing.

The camps in Greece

The management of the migrant camps, designed to confine all those stranded in Greece since 2015, illustrates the intensification of the everyday practice of borders in recent months through subsequent crises, culminating in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Today, 120,000 migrants are trapped in Greece; half of them women. Most are confined in camps and other camp-like spaces in locations with increasingly hostile local populations. The conditions there are particularly unsafe for women and girls, LGBTQI+ individuals, children and people with disabilities and chronic illnesses because emergency response policies and legal frameworks are not gender-, age- and ability- responsive, putting these already vulnerable groups at even more at risk.

Recent efforts to move people from the severely overcrowded camps on the islands were forcefully resisted by local authorities and populations in destination cities across the country. Similarly, efforts to expand existing facilities and build new closed camps on the islands were met with ferocious reactions by locals, leading to severe clashes with riot police. These explosive conditions have led to migrants, NGO workers and even journalists on the islands becoming targets of attacks and abuse, often by newly mobilized fascist militant groups.

These tensions have come to exacerbate the dire conditions that migrants are forced to endure while living in camps: overcrowded facilities, improvised housing, highly unsanitary and unsafe living conditions, little to no access to essential services such as physical, mental and reproductive health and legal counseling.

The sustained confinement of migrants in remote locations where they are not wanted together with their portrayal by the media and the authorities as threats to local communities, has further constrained their movement, turning simple and routine tasks such as grocery shopping into dangerous endeavors.

In early 2020, new tensions at the border with Turkey intensified this war-like atmosphere, as the number of those trying to cross rose sharply. This latest ”border crisis” moved the authorities to take exceptional, extraordinary and disproportionate measures, such as the suspension of asylum applications for the month of March, which is not provided for in EU and international law.

The Greek authorities and media labeled the situation a planned invasion and infringement of national sovereignty by Turkey. The police and the military were deployed in an already heavily militarized border zone while armed militias and vigilante groups mobilized, hunting migrants and pushing them back. The police and the army fired live rounds at those trying to cross into Greece, killing two men, Muhammad Gulzar and Muhammad al-Arab, on March 4, and leaving many more wounded.

One day before, Ursula von der Leyen had visited the area, crediting the Greek authorities for being “our European shield” and pledging €700 million more in aid. Under the unrelenting obsession to avoid a new crisis, the EU legitimized the violent practices and unlawful actions of the Greek authorities.

Conjuring the emergency, all the migrants that arrived in March were detained and confined in improvised, temporary and mobile spaces, such as naval ships, under re-traumatizing conditions, in violation of their rights and without access to legal counsel. The EU’s embrace of such unlawful and illegitimate practices against border crossers increasingly embroil migrants in the geopolitical games between the EU and Turkey. Following the policy direction sealed by the 2016 EU-Turkey Statement, the EU today continues to infringe the rights of migrants in a structural way, prioritizing the externalization and fortification of its borders while transferring the pressure to peripheral member states.

For those living in the camps, the policies to stop the spread of COVID-19 meant even further restrictions to their already very limited freedom of movement. The camps on the mainland and the islands were completely isolated, with only essential personnel allowed to enter. With lockdown extended until June even though it is lifted for the rest of the county, camp residents are de facto denied safe accommodation, access to health care, food security and support.Information regarding the virus and how to protect themselves is scarce, and migrants have self-organized in an effort to deal with everyday issues collectively: the Moria Corona Awareness Team, bringing together teachers, pharmacists and other professionals living in the Moria camp on Lesbos, raises awareness about the virus everyday and tries to tackle issues such as waste management and the prevention of fires.

Public health measures in the camps are not so much for the management of the pandemic but against migrants. These include limited movement of migrants from the camps to the neighboring urban centers to meet their needs, withdraw cash, buy food and medicine and visit the doctor. The timetables set seem unreasonable and impossible to manage in a way that secures fairness, decency, and equal and safe access for vulnerable groups, for whom simple everyday tasks may already subject them to risk of harassment, exclusion and even violence. Migrants can move outside the camp only from 7am to 7pm, in small groups every hour exclusively on special public transport routes of “controlled and restricted traffic”, under the supervision of the police. It’s not hard to imagine scenes of tension when boarding those buses, especially in camps housing thousands of people. Under such volatile and even violent conditions, how can access to the town be secured for the most vulnerable?

Finally, as everywhere in the world, the lockdown has had a disproportionate impact on women, who, due to structural gender-based inequalities, are bearing the brunt of care work in the family, while access to much needed sexual and reproductive health services de facto is denied due to the lockdown.

Clusters of COVID-19 infections eventually appeared in three different facilities around Greece, in the camps of Ritsona, Malakasa and Kranidi. These facilities were quarantined for 14 days, but the infected individuals were not evacuated, thus endangering other residents. The result was that in all three cases the quarantine was extended because of new infections, while the police and the military were deployed to ensure its enforcement. This governance turned the already “unworthy” figure of the “illegal” migrant into an additional threat: a threat to the health of the national body.

In Kranidi, a hotel rented by the IOM to accommodate 470 migrants, the cluster involved 156 infected individuals. Contact tracing revealed that some migrant women, potentially underaged, residing in the hotel were sexually exploited. The media quickly picked up on the story, using racist, sexist and misogynistic language to paint the female migrant as a threat to the public health and the sacred institution of the family. This builds on a long history of routine and systematic stigmatization of migrants, often labeled as “public health bombs,” portrayed as culturally and religiously inferior, hence threatening a certain idea of European values.

The often racialized figure of single men tend to be portrayed not simply as less vulnerable but also as more dangerous, while women are constructed as victims or as carriers of diseases when engaged in life-sustaining, often forced, activities, such as sex work.

As a result, the management of the pandemic has effectively legitimized the continued confinement and isolation of migrants, cutting them off from essential social and political networks and economic opportunities. The mobility of migrants is implicitly linked to the risk of spreading the virus and their portrayal as vectors of disease has led to the justification of their confinement and isolation on medical grounds.

The state instrumentalized the public health emergency to advance already existing plans and strategies regarding the confinement of the migrant population, while simultaneously showcasing their confinement to promote the state’s efficiency and authority in response to the pandemic.

The previous emergency at the Greek-Turkish border framed illicit border crossing as an issue of national security, depicting migrants as an asymmetric threat and instruments of the Turkish state. The confinement of migrants as a measure against the spread of the virus subsequently reduced the management of migration, asylum and border control into a purely technical issue to defend the public health.

As a result, the militarization of borders was consolidated in the name of border security while violence against migrants and their allies was legitimized. Framed in this way, the border has become a renewed, intensified and urgent field of political struggle.

Border politics

If the EU border is not a place but a dispersed set of practices, institutions and knowledges that are enacted every day during routine encounters, then its contestation should also focus on the everyday. Our aim should be to confront and disrupt the logic and ideology that shape borders today through everyday practices of care and solidarity. In our practices we should be directly engaging with the racial, patriarchal and colonial assumptions that underpin the border and humanitarian regimes in order to avoid, even inadvertently, further disempowering migrants, compromising their autonomy and co-opting their voices.

The engagement with the border in everyday life is a primarily feminist imperative and draws on feminist insights and methodologies. Engagement in politics of border resistance and solidarity with border-crossers is an embodied experience and practice, one that is centered around care. Recent experiences of solidarity with newcomers in Europe have demonstrated the vitality of such everyday struggles born out of existing care networks and social infrastructure. The migrant housing and solidarity projects in Athens between 2016 and today have accommodated thousands of transiting and stranded migrants. Born out of existing care networks that made up the city’s social infrastructure from below during the years of the crisis, these projects eventually gave rise to new alliances and struggles, through politics of everyday life, friendship and collective living.

Such practices are particularly pertinent in regards to the increasing precarity faced by millions of workers worldwide due to the COVID-19 pandemic, exacerbating existing inadequacies and inequalities in health and social services, food and housing security.

The exceptional surveillance of mobility and labor, until recently enforced with violence mostly on migrants at and within state borders, has now been extended to the entire population for the governance of the pandemic. This forces us to appreciate, and even to share, some of the vulnerabilities produced by the virus, previously affecting mostly sexual, racial or migrant minorities.

On the other hand, the grassroots responses to this crisis have highlighted the significance of social reproductive work and the absolute necessity of care labor, usually done by women at home and thus devalued, invisibilized and individualized. But by addressing social reproduction as a collective issue with collective solutions — a fundamental feminist anarchist concern — we can build on, and expand existing social networks of solidarity, mutual aid and care. In this way, our social infrastructure, built from below, can accommodate all those living on the fringes, not only surviving under the radar but molding alternative experiences, co-constituted by all those that inhabit that social space.

Therefore, subversive border politics are found in everyday practices of care, in the production and sharing of information, knowledge and survival tricks by and for migrants and non-migrants. Everyday practices of resistance, through solidarity and care — collective kitchens, time banks, housing squats — especially in the context of shared needs and precariousness, can reshape the very practice of antagonism to the state: moving away from more confrontational and militant tactics and towards practices that meet basic needs of migrants and non-migrants alike, such as food, shelter, health, mental health, caring for the elderly and children.

By collectivizing care, we begin to dismantle the oppressive rationales of the border, aiming to engage a broader range of people in solidarity and care practices for the good of the whole community. In this way, we contribute in blurring the boundaries, closing cleavages, and unsettling categories and binaries that are often deeply ingrained in migration and border control.