Via Black Rose Anarchist Federation

In an era of pandemic and mass protest we are witnessing an uptick in political militancy, from attacks on police stations and the seizure of space to wildcat strikes and rent strikes. These are promising developments, but the balance of class forces remains lopsided, evidenced by the massive corporate bailout package, countless workers being exposed to unsafe working conditions, and mounting unemployment. While COVID-19 has limited our ability to respond to the crisis, we need to discover creative ways to intervene in the current moment to meet the urgent needs that have arisen and think through how to prepare ourselves for the post-pandemic period—whenever that may be—to tip the balance of forces in our favor. We will have to defend ourselves against austerity and other attacks, but we can’t limit our activity to a defensive posture. In this piece, Spanish anarchist Lusbert Garcia offers a framework for orienting our organizing efforts toward strategic sectors in society and makes the case for linking these sites of struggle over time into a broad-based, multisectoral movement that can put us on the offensive.

Translation by Enrique Guerrero-López and Leticia RZ

By Lusbert Garcia

By making a brief analysis of current social movements, we can see that they do not work together, that is, in a synchronous way between movements that operate in different areas of struggle. First off, this article is a complement to the translation of the article “A debate on the politics of alliances [Un debate sobre la política de alianzas]” where I talk in broad strokes about the numerous areas or sectors of struggle and think through how to build a multisectoral movement, that is, a broad movement made up of a network of social movements that work in coordination in different sectors and at the same time are articulated based on the common denominator of autonomy, feminism and anti-capitalism.

We know that the root of all problems lies in the capitalist system and the modern states that support it, and that this economic, political and social system supports a production model based on private ownership of the means of production and private benefit as a fundamental principle. All this constitutes what we know as the structural, and its manifestations in all areas of our lives, which is known as the conjunctural, of which we could mainly highlight: territory, labor, public services, accommodation and repression. When we analyze the political-social space, we must recognize the conjunctural problems that manifest as a consequence of the material structure:

- The territorial issue would include within it the spheres in which the interests of the class which rules over the territory enter into conflict with those of the working class. It is the physical space in which all struggles will take place, so we can highlight the following areas: neighborhood or district if we talk about cities, rural and land struggles if we talk about undeveloped or non-industrialized areas, and we could even include the national liberation struggles for the self-determination of peoples against imperialism. Environmentalism and food sovereignty would also fall into this category.

- Labor here would constitute one of the main axes of class conflict. It is the battlefield where capital and labor meet most directly. In this area we can mention the workers’ movement that is articulated around unionism. Although we have to differentiate between unionism that advocates social peace—that model that always leads to class conciliation, betraying the working class—and the revolutionary or class unionism that advocates the exacerbation of class conflict in the workplace.

- The fight for housing is a movement that goes back a little over a century during the rural exodus caused by industrial development and the creation of working-class neighborhoods. Today, with capitalist restructuring underway again in advanced capitalist countries and those in development, access to housing is again a social problem that affects the working class as it finds itself with less economic capacity to face mortgages and rents, as well as access to decent housing. Faced with this problem, movements against evictions have sprung up in many countries, as did the squatter movement a little earlier.

- As for state public services, in the face of this phase of capitalist restructuring, markets are increasingly interfering with these services through budget cuts, outsourcing and privatizations. Here we can mention: Education, Health, water and sanitation, public transport, and pensions, among others; and the respective social movements that arise in response to cuts and privatizations, such as the student movement, White Tide [1] and other movements against the privatization of water, the fight against increases in rates on public transport, etc.

- Last but not least, all opposition movements receive state repression; therefore, it is important that we begin to see repression as an obstacle and a social problem that seeks to curb our social and political activities while serving the ruling class to perpetuate its dominance. In this regard, we must speak about the anti-repression issue and face repression collectively and outside of our own militant circles, as yet another social movement.

Within each sector there are also subsectors. For example, within the student movement, those who organize in the University will not be the same as those from professional training and those from secondary education. In the labor world, the labor movement would be divided between the various productive branches such as construction, transportation, services, etc. In other words, the substantive demands of the student movement would be the same regardless of the subsector, even if they differ on particular and specific issues. This is also seen within the labor movement, where the substantive demands can be the increase in the minimum wage, reduction of working hours, etc., and the particular demands would be improvements in the collective bargaining agreement, for example.

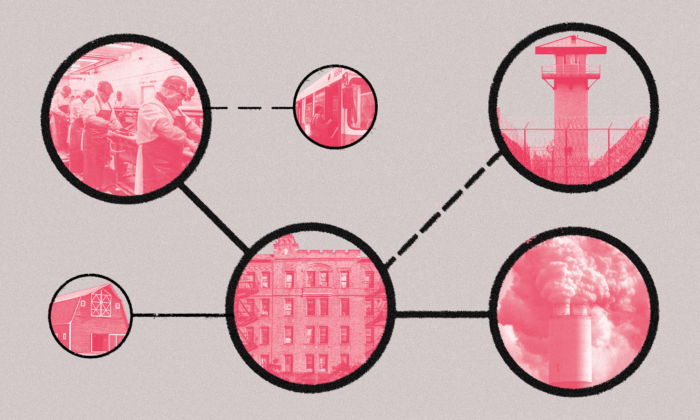

However, we must not take all these sectors in struggle as isolated elements, but as a set of conjunctural battle fronts that have their origin in the capitalist system, and therefore, connected to each other. And here comes the main question: how to connect these sectors in struggle under a common political-social denominator based on anti-capitalism, feminism, anti-racism and internationalism. Looking for the connection between various sectors is not very difficult. Let’s see some examples:

- Neighborhoods and the fight for housing as well as the squatter movement.

- Food sovereignty, environmentalism and the struggle of the peasantry for their lands.

- The student movement and the labor movement. This is already a classic.

- The movement against rising public transport rates with women workers in the sector.

- Anti-repression fronts with neighborhoods.

In the previous examples, we can see that they have points in common with each other, which can lead them to converge and overcome sectoriality, that is, working in isolation in a specific area without coordination with the rest. We can even go a little further and connect neighborhood movements, squatting, anti-eviction with the municipality, with the workers and student movements, constituting a network of movements that could unite with the peasant and indigenous movement (this would occur in Latin American countries mainly; Europe or the US would be very difficult). And since all these social movements will suffer repression along with the political-social collectives and organizations, it is important that the anti-repression struggle be articulated from the neighborhoods, neighborhood associations, etc.

A century ago, in full industrial development, the labor movement occupied the central pillar of class and social conflict. Today we can no longer use this premise as no front is gaining greater importance than the rest, which leads us to discard the hierarchy of struggles to put on the table the idea-force of networked movements. When we arrive at this point, it is when we must consider multisectorality, that is, articulate common discourses that allow the alliance of the various sectors in struggle, respecting their autonomy but maintaining common bases on which to build broad movements, escalate conflicts and go from resistance, that is, defensive positions, to offense.

The limitations that sectoriality has leads us to think about transcending the struggles of specific scopes to wider movements to articulate an offense. I developed the issue of multisectorality precisely due to the limitations that each sector in struggle had, and therefore, in isolation they could not go beyond the defense of social problems that specifically affect that sector. Before talking about the offensive, we will address the principal limitations of each sector.

- The labor sector. In my previous article I pointed out that currently the labor movement is no longer the central axis of struggle, but one more among the many that exist despite being the one where the capital-labor conflict is most directly confronted. The main limitation in the labor movement is the economic sphere. Trade unionism itself cannot become a revolutionary movement, since it is limited to the field of the productive model within the capitalist system. However, unionism can serve to organize the working class and aspire to seize the means of production and self-manage them. However, if self-managed projects do not emerge from the market economy, it will not be a transformation at the root.

- Student movement. In the educational environment in which they operate, students will find a great limitation in terms of claiming an alternative model to the current one increasingly oriented towards markets. Thus, the educational models inspired by free teaching within a capitalist society are very limited precisely by the regulations of the States and the funding they require. Such an educational model is unthinkable in class society.

- Public services. In this area, so controversial among anarchists, the limitation lies precisely in the financing. Like many things in this capitalist society, if we do not want Health, Education, supplies and such to be privatized, such financing could only come from the general budgets of the State, without allowing the interference of private companies. Although under their management they may come to carry more weight in the community, rather than under the State’s administration.

- The fight against repression. This is the area where the most economic, physical and psychological wear and tear is involved due to the few results that are achieved despite the great efforts invested. This is a confrontation against a greater force, which is the armed wing of the State. Its main limitation is the need for very extensive support networks to overcome the isolation and overload of militancy, as well as the high risks they run.

- Rural and peasant movements. Talking about such movements in advanced capitalist countries would not make much sense beyond small organic farming cooperatives, whose limitation resides in the little weight that the field has in addition to a total absence of peasant movements. But this is not the case with Latin American countries in which there are strong peasant and indigenous movements. Although the peasantry fits within the working class, its scope of action is not the same as that of the urban proletariat, in addition to the fact that the immediate conflicts in the fields are not the same as in the cities. Furthermore, even if the peasant and indigenous movements get land and constitute autonomous territories, they are on the periphery of the capitalist nuclei that are the cities.

- The struggles for housing and neighborhoods. Although one of the strengths of these struggles is the construction of the local social fabric, its main limitation is the territorial one, since they exist at the local level. However, it has great potential if they connect with other sectors in struggle.

The limitations that we see in each sector in struggle means that they only adopt a defensive posture, trying only to resist the onslaught of neoliberalism. If we look at the enemy, we can see how since the 1970s neoliberalism, since it emerged as a way out of the crisis then, is continuously going on the offensive: attacking the Soviet bloc first and seeking alliances with European states, continuously attacking labor and social rights, supporting and promoting coups in Latin America and Central America, etc., until today with the implementation of the euro and the EU, pushing back on labor rights in each labor reform, reaching into state public services such as Education, Health, pensions, water, etc., and now with the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) that will allow less regulation in environmental protection, more setbacks in labor rights, more power for multinational corporations and investment funds with private supranational courts that can judge governments that harm their profit rates, among other things.

That is why we ask ourselves, how can it be that neoliberalism is continuously on the offensive while the social movements are always on the defensive? And this is a problem that comes mainly from the lack of political alliances between sectors built under a common discursive denominator, that is, a road map with proposals and demands that allow progress, not just resistance. And this advance can only come through the articulation of a multisectoral popular movement, because that is the only way we overcome the limitations that come with each sector in struggle. I want to note that this is only a sketch for the purpose of serving as a contribution towards building future roadmaps and it may possibly be missing several things. I will put some brief examples below:

- So we will start with the student movement, which has many connections to the labor market, since most students will enter the job market after their training. The line is increasingly blurred between the labor market and training, which is seen in business practices both in vocational training and University. Furthermore, with this new labor panorama in which continuous training and the concepts of retraining were introduced, in reality they require the “recycling” of workers to follow the demands of competences in the labor market. That is why the student movement necessarily has to have connections with (class) unionism.

- Now, in the face of job insecurity, unemployment and the diminishing purchasing power of the working class, access to decent housing is also worsening, as is the problem of evictions, so they will necessarily have to connect with the struggles for housing and also contribute to building a social fabric that breaks isolation, putting mutual aid and solidarity into practice in neighborhoods. Also, due to the gentrification suffered by neighborhoods due to real estate speculation and the conversion of neighborhoods into spaces for consumer leisure, there is a need to open political and social spaces to counteract the consumerist and hyper individualistic culture of capitalist societies and to constitute focal points of resistance.

- And since every protest movement will receive state repression, it is essential that the anti-repression issue be inserted in all sectors and be made visible as a problem that affects everyone and from which everyone can suffer.

An offensive strategy begins by recognizing that each area of struggle and its problems are not separate and specific problems, but rather originate from a common material structure, which is capitalism in its neoliberal phase and the modern states that support it. Said offensive strategy does not consist in attacking the symbols of capitalism and the State nor in the vanguard positions of a militant minority, but must arise from the political articulation of the entire popular movement, which is not only capable of winning victories in every sector, but rather have the capacity to materialize alternatives that transcend the sector itself. For example, to be able to start alternative educational projects, it is necessary not only to seize the centers for community management, but also to have insertion in the neighborhoods and in the labor market promoting the values of the commons, to keep them from remaining marginal projects. From this point on, the political articulation of the movements should focus on programs that respond to the needs of the moment and implement them in each context, based on anti-capitalism, mutual aid and solidarity, autonomy and horizontality, as well as feminism, internationalism and anti-racism.

We are aware that we are still very far from being able to put an offensive strategy in place against the capitalist system, and this is precisely because, as anarchists in particular, we are not building the social bases that would be the social force that allows us to articulate ourselves as a political force. For this reason, we must consider social insertion as the first step in the ambitious task of revolutionary social transformation. We must be able to respond to immediate problems and empower social movements as a short-term strategy to pull off small victories and draw strength from them in order to aspire to greater objectives. The offensive involves direct political-social combat against the capitalist system and the sharpening of the class struggle promoted by a broad and politically articulated popular movement.

For any popular movement to go on the offensive, it is also essential that they have roadmaps and political strategy. What is political strategy? Strategy, in general, is a set of tactics aimed at achieving a goal in a complex environment where a multitude of factors come into play. And specifically, political strategy has to start from conjunctural analysis, a tool by which detailed information is extracted from the environment around us in order to intervene on the political and social stage in order to achieve a series of changes, allowing us to move toward achieving our ultimate goals. From that necessary conjunctural analysis, we can see that our final goals are currently unattainable, at least in the medium and long term, which leads us to set intermediate and more achievable goals, that allow us to advance positions. This is where political strategy enters.

The absence of a political strategy makes it so that movements pull by inertia, that is, they move defensively in the face of the need to stop the attacks of the ruling class without knowing how to counterattack. In other words, they are forced by the conjuncture and not driven by a confrontational perspective. The expression “something must be done” perfectly illustrates this problem, which manifests itself in reality through action-reaction methodologies; that is, of responding only when there is a significant attack, of vague and very generalist or conservative proposals for wanting to go back to an earlier phase or maintain the current state of affairs The main consequences of the lack of political strategies are movements becoming disoriented and adrift (in the worst cases), being always influenced by the conjuncture, encountering dead ends, volatility and routes that lead back to zero. Within the libertarian movement itself, the dynamic is similar, although efforts are already being made to overcome it with new initiatives that have recently emerged. Lack of political strategy has condemned us to marginality and isolation.

The need to overcome “something must be done” involves having a strategic vision; that is, overcoming the defeatist airs that mobilizations through inertia entail and putting strategies for action and intervention in the political and social scene on the table. For this reason, we have to ask ourselves something that Lenin once did: “what is to be done?” Adapting it to our situation, that would be: what is to be done with each sector-wide problem (housing, public services, work, education, territory)? What is to be done in the face of the ineffectiveness and illegitimacy of rival political forces —which are not our enemies, because the enemies are the political forces of the dominant one that is in direct confrontation against us? What is to be done in the face of cuts in social rights in general and the continuous neoliberal offensive? What is to be done in the face of opportunism and the rise of fascism? … the answers to these would serve as the basis for preparing roadmaps and programs focused on social intervention. From this strategic vision, we will see the various political options as forces, whose real strength will reside in the legitimation given to them from the grassroots. One must also keep in mind that political forces will tend to occupy as much space as they can, meaning, if a political force leaves a space, it will be taken up by another. Thus, if there are no alternatives proposed outside of institutions, betting on autonomy, confluence and coordination, and the radicalization of social movements under common discourses that aim at overcoming capitalism and other forms of domination, it will not take long for these movements to be co-opted by political parties that adapt their discourse to bring social movements to the polls, with their consequent demobilization and assimilation by the system. And this is what is currently happening.

For this reason, the offensive approach not only involves building a multisectoral movement, but also adopting political strategies that allow the advancement of the entire popular movement. The offensive is inseparable from the political strategy, in fact, it is from the political strategy that we consider these premises of offense and multisectorality. And I would even add that strategic vision must start from the first moment in which we aspire to a radical transformation of society; that it must aim to build, strengthen and promote the autonomy of social movements; that once this task has been carried out, it must aspire to an articulation of multisectorality and therefore, to build a political force with real strength capable of achieving changes not only in this situation, but in transforming the structure (capitalist relations of production, neocolonialism, heteropatriarchy, white supremacy, etc …). In general, it is focused on increasing our strength as oppressed social classes.

Before finishing, to better illustrate the concept of political strategy, we could look at a hypothetical scenario in which, on the one hand, the main unions go through a general delegitimation and go into decline due to loss of membership, the disillusionment and distrust of the working class, and the loss of its of ability to convene; and on the other, the percentage of unionized workers is relatively low (let’s say around 10%). Given this situation in which a rival force is weakening, we must take advantage of this delegitimation to fill the gaps they have left. In this case, the best thing to do would be for class struggle unions to position themselves as functional tools for the defense of the interests of the working class, to encourage the participation of the membership and sympathizers, to know how to respond swiftly to job insecurity, temporality and subcontracting in all productive sectors, from small businesses to large companies and, above all, to extract victories, even small ones; achieve them, maintain them and aspire to bigger ones.

We could also escalate this hypothetical scenario and arrive at the confluence of the labor movement and combative unionism with student struggles and struggles for decent housing as well as with the squatter movement. And another hypothetical scenario, within the libertarian sphere, would be to put aside as far as possible the ideological confrontation with other political tendencies within the left and opt for escaping marginality and outnumber them in real force before other tendencies do, which leads us to work in the social field through insertion in social movements, to respond to immediate social problems and promote struggles, to achieve the necessary social base to really advance popular movements and give them as libertarian a character as possible, capable of standing up to the capitalist system by creating confrontational alternatives.

In summary, political strategy aims to push by creating political alternatives that aspire to overcome the existing order. Political strategy also implies some cunning and a lot of ambition, inserting ourselves into the material reality, taking advantage of the opportunities that are presented to us and intervening or attacking, not symbolically but in a systematic and planned way; having consistency in our political and social activities, and not leaving everything to improvisation; accumulating experiences so as to not have to start from scratch; and not attacking through brute force, but with the force emanating from popular self-organization and its political articulation. In this sense, political strategy is what gives content to the offensive.

Lusbert Garcia is an anarchist communist writer based in Spain. This article is based on the merger of three articles previously with Regeneración.

If you enjoyed this piece we recommend another piece by Lusbert Garcia, “Strategy and Tactics for a Revolutionary Anarchism,” or Mark Bray’s “Horizontalism: Anarchism, Power and the State.”

Notes

1. White Tide was an anti-privatization movement that began in Madrid in 2013 and spread throughout Spain.