This article originally appeared in the Institute for Race Relations: https://irr.org.uk/article/policing-of-black-youth-projects/

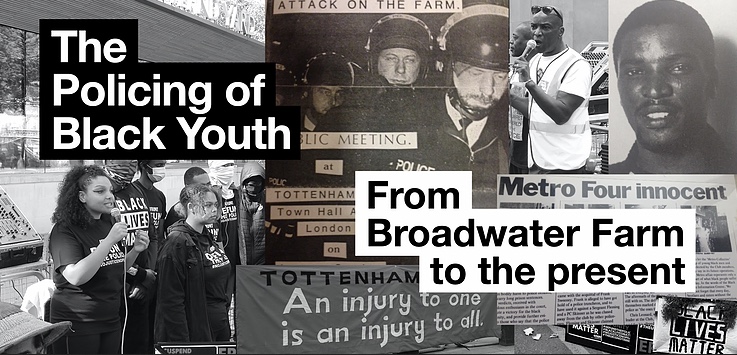

Jessica Pandian examines the historic policing of Black youth projects in London, from the seventies to the present day, and associated community resistance.

Black Lives Matter has highlighted the over-policing of Black British youth. And Black History Month provides the ideal opportunity for an exercise in historical retrieval. Drawing on an interview with veteran Tottenham campaigner Stafford Scott, observations at BLM protests, and historic cases of the policing of the Notting Hill Metro Youth Club in the 1970s and the Broadwater Farm Youth Association in the 1980s, the author reflects on the parallels and continuities between past and present. Ultimately, this piece reveals a lesser-known, but lengthy history of the Metropolitan Police Service targeting Black youth projects.

On Friday 7 August 2020, in a sweltering 36-degree heat, The 4front Project, a member-led youth project, were busy at their base at Grahame Park Estate, north-west London, a day before a peaceful protest against the over-policing of Black communities was due to take place in Tottenham. However, at 2.40 pm police officers carried out a stop and search on a 14-year-old boy on the estate – and then arrested him.

According to 4Front, young people from the estate alerted 4front staff of the arrest. 4Front say that they then attempted to engage with officers so as to determine the reason for arrest, but that officers refused to engage. Young people and 4Front members proceeded to sit in the road and block the police vehicle, and police summoned further police units.

Eyewitnesses say these police units were the Territorial Support Group (TSG). What happened next is subject to fierce debate, but a further two people, two 4Front youth workers, were arrested on suspicion of obstruction of a constable. The police vehicle left the scene. A group of approximately 30 – 40 people from the estate followed the police on foot to Colindale Police Station where they demanded the release of the arrested individuals. A section 35 dispersal order was put into place, and further officers were called to disperse the crowd. Another 19-year-old man was arrested on suspicion of assaulting a police officer. Later that day, the police released all four individuals from police custody under investigation.

Genealogies of police racism When referring to histories of police brutality in London, the iconic case of The Mangrove, a vibrant Black Caribbean restaurant which was repeatedly raided from 1968 to 1988, is often cited – which, whilst undeniably important, needs to be contextualised in the deliberate police targeting of other distinct Black spaces.

In fact, in the same time-frame the police targeted The Mangrove, Black youth projects across London were attacked with the same oppressive tactics. This piece will uncover the lesser-known, but lengthy history of the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) targeting, swamping, and raiding Black youth projects. By digging deep into past layers of police violence against Black youth projects, we might become more attentive to the contemporary targeting of Black youth projects and begin to imagine the future relationship between the MPS and Black youth projects[1].

Specialised Units: against the people In the case of Notting Hill’s Metro Youth Club, the police besieged the premises in 1971 on the pretext that a Black youth who had committed robbery had escaped into the club. The way in which the alleged presence of a Black robber rationalised the police’s attempt to search the Metro Club, and when the Black youth resisted, to enlist the Special Patrol Group (SPG) who assailed the West Indian youth inside and arrested 16 of them – encapsulated the zeitgeist, as it was during the seventies that the state and the media worked in tandem to create a racialised moral panic over street crime in order to legitimise the aggressive policing of Black communities. By the mid-1970s, this had morphed into the generic folk devil of the ‘mugger’, with the critical point arising in 1973 when Paul Storey, a 16-year-old youth from Handsworth, was sentenced to twenty years for stealing five cigarettes and 30p.

The deployment of the SPG, a centrally-based mobile force, equipped with riot gear and firearms, the ostensible purpose of which was to police serious public disorder and crime, to the Metro Club was also a sign of the times. The constructed crisis of Black street crime had facilitated the mobilisation of SPG vans and cars en masse into Black communities where they regularly orchestrated raids on their public and private spaces; performed mass stop and search campaigns; and utilised violence against them. Two of the highest-profile examples of the SPG engaging in such tactics were during the 1979 Southall Protests and Operation Swamp 1981.

In the year of ‘Swamp 81’, localised public order units were also created. Named Instant Response Units, these units emerged onto the streets and accompanied the SPG in their crusade against Black people. And so, when a crowd of residents at Broadwater Farm Estate gathered outside Tottenham Police Station in 1982 to protest the arrest of a member of the Estate’s Youth Association for burglary – it was the Instant Response Unit who saw the crowd, attacked the demonstration and arrested four members of the Youth Association.

Council estates as the frontline The targeting of Broadwater Farm Youth Association in 1982 was emblematic of how council estates, where a great proportion of the Black population lived, and which were portrayed as cesspits of Black gangsterism and drug-trafficking, began to be singled out for aggressive policing. The transparency of this exercise lay in the way that the MPS drew up a list of 20 ‘target’ estates in 1986, categorising them from ‘high’ to ‘low’ risk based on criteria such as an estate’s ‘ethnic mix’ and the perceived severity of gang conflict. Broadwater Farm Estate was classified as ‘high’ risk. This concentrated operation fitted into a broader spatialised police project, whereby areas with a high BME population such as Tottenham were designated as ‘high crime’ areas, which intensified police presence in these areas[2].

Broadwater Farm Estate Photo source: geograph Photo credit: Marathon (adapted from original)

Into the present, the police have sustained theirspatialised version of racial profilingby continuing to target council estates. The racially discriminatory cartographic practices of the eighties live on today through the MPS mapping of ‘gang-territories’, which are layered onto council estates in areas with dense BME populations, such as in Haringey. Meanwhile, the Territorial Support Group (TSG), which replaced the SPG and IRU, has kept alive the legacy of its predecessors by operating in ‘hotspots’,inferredas those with serious levels of gang-related violence – i.e., in working-class BME spaces, such as council estates.

On top of this, the MPS has created new units to target gang-related violence and knife-crime. When, in September 2018, London mayor Sadiq Khan established aViolence Reduction Unit (VRU) at City Hall, he promised that it wouldwork alongside police enforcement, in particular with theViolent Crime Taskforce, also funded by City Hall, with an annual budget of £15 million and 272 officers in 2018. The VRU, which draws on the Scottish public health model which treats crime as a disease, is a ‘multi-agency’ initiative, involving partnership between The Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime, community organisations, and health and education sectors, with the aim of diverting young people from criminal activity. Moreover, the VRU adopts a ‘hyper-local, place-based’ approach – explicitly mentioning ‘housing estates’. Outwardly, the VRU may appear to be a holistic endeavour, but in the context of historic police aggression against Black communities; it represents the percolation of racist policing into all aspects of life in BME areas. Meanwhile, the Violent Crime Taskforce, which was established in April 2018 to fight knife crime and ‘serious criminality’, is all about police enforcement. Furthermore, the latest addition to the MPS’s specialised units –Violence Suppression Units(VSU) – the appearance of which on the streets of London coincides with the Coronavirus Act 2020, injects intense police activity into 250 of London’s ‘microbeats’: areas identified as ‘synonymous with drugs and violence’.

And so, what is the effect of all this? The absolute saturation of MPS frontline officers, TSG units, VRU units and VSU units (amongst others) on council estates in BME areas. On this subject, Temi Mwale, founder and Executive Director of the 4Front Project, has previously expressed how the Black community experience this ‘saturation’ at Grahame Park Estate, saying, ‘Arrests [of young people] happen here every single day.’ Further to this, she has said,

‘When it comes to the Black community, we only experience the police force. We don’t experience the police service.’

The deep-rooted association of council estates with drugs and their subsequent intense policing explains how (ostensible) suspected cannabis possession[3]served as the justification to draft in a police helicopter and raid Broadwater Farm Youth Association in 1986. Where once before, it was the folk devil of the Black mugger which legitimised police violence against Black communities, from the eighties to the present day, it has been the folk devil of the Black, knife/gun-carrying drug-dealing gangster.

Black Lives Matter Photo taken by author

Youth Associations: in the eye of the beholder

The targeting of council estates explains to a certain extent why youth associations attached to estates are subject to police violence, but it doesn’t entirely get to the crux of why youth associations in particular are targeted. Speaking with Stafford Scott, veteran campaigner, former Broadwater Farm youth worker and co-founder of the Broadwater Farm Defence Campaign, the concept of a double-edged sword arose when talking about the Broadwater Farm Youth Association. On the one hand, Stafford elucidated how the Youth Association, established by matriarch Dolly Kiffin in 1981, provided a refuge from racism for Black youth of the estate and the wider neighbourhood. However, on the other hand, Stafford described how the police – far from seeing the Youth Association as the empowering, safe-space that he spoke so affectionately of – viewed the congregation of Black people under the Youth Association, which was rooted in ideals of Black self-governance and which was ‘demanding opportunity for young people to be able to participate in mainstream activities’, as ‘something that challenged the status quo’. Stafford believes that the creation of the Youth Association is the reason for which Broadwater Farm Estate became distinguished by the MPS as a ‘symbolic location’ for policing between 1982 and 1987. Elaborating on this, Stafford ventured an opinion on why Black youth projects have been identified by police as target locations:

‘I just think that police have an issue with young Black people who try to do for self. Police wanna criminalise and contain Black people, control how we move and where we go. And they have a real issue with Black empowerment. And what 4Front wants to do and what the Youth Association was all about, [it] was all about empowering young people who happen to be Black.’

Mass criminalisation

Throughout what I mention below, it becomes apparent that it is not just the one or two ‘suspect’ individuals who are met with the force of the police. As with the Metro Youth Club in 1971, all those who resisted police entry ended up being criminalised to the same degree as the original suspect, resulting in many being arrested. Looking at other cases, we see the same happening. In 1972, a youth club leader and pastor who protested the raiding of his North London youth club by 100 policemen in 30 vehicles was beaten by officers and bitten by police dogs. Then, outside Tottenham police station in 1982, we saw how the police assaulted and arrested the estate’s youth workers who were protesting the arrest of a member of the Youth Association. The pattern is clear: anyone who stands in solidarity with a suspected criminal, becomes a suspected criminal.

Kusai Rahal, a 4Front Project youth worker who was arrested and issued a coronavirus lockdown fine in April when he arrived at a police station to act as an ‘appropriate adult’ for an arrested minor, articulated how youth workers like himself become ensnared in the web of criminalisation,

‘By virtue of me working with a group of criminalised young Black boys, I myself as a youth worker, just by being in proximity to them and supporting them, I’m also criminalised in that process.’

One struggle, one fight

Despite the consistent targeting of Black youth projects, one thing has always remained consistent: resistance. We see this in the way that youth project members and estate residents continually come together to resist police violence. As we have witnessed, this resistance has taken on diverse forms: the blockading of police entry into the clubs; the remonstrating with officers; and protesting. In the context of profound state anti-Black racism, the very existence of Black youth projects, which aim to empower and address the needs of Black youth, must also necessarily be viewed as an act of resistance.

Stafford Scott Speaking outside Tottenham Police Station 8 August Photo taken by author

Encapsulating the history of shared struggle, in the last few months, the 4Front Project, Stafford Scott, The Monitoring Group, Black Lives Matter UK, Stopwatch and Tottenham Rights have united forces to stage protests against the over-policing of Black communities. In a way which very visibly aligned the struggles of Tottenham with those of Grahame Park Estate, at the firstprotestheld outside Tottenham police station on 8 August to symbolically mark the 9-year anniversary of Mark Duggan’s death, Temi Mwale spoke powerfully against the over-policing of the Black community. With Stafford Scott by her side and the 4Front team surrounding her, she shouted,

‘We want an immediate end to the over-policing of our communities! An immediate end to the harassment, the abuse, the assault, the violence! It must end now!’

Talking to Stafford about his working relationship with Temi, which has its origins in the Justice for Mark Duggan Campaign, Stafford expressed how he sees the struggles of Broadwater Farm Estate mirrored in the struggles of Grahame Park Estate; and in a similar way, sees himself in young Temi Mwale. As he commented candidly, ‘Different location – but same struggle, same fight’. Reinforcing this, he added,

‘These days are so similar to the eighties it’s quite unbelievable. The rise in the issues around policing; the rise in the nature of more brutal, hostile and violent policing. All of these things just chime with what was happening in the eighties.’

The 4Front Project at BLM Protest 12 September Photo taken by author

New struggles: gentrification

In the context of anti-Black racism, the Metro Youth Club was demolished in 1979 to clear the way for social housing. And now, in the context of anti-Black racism and neoliberalism, we see how the targeting of Black spaces is compounded by state-led gentrification projects. Indeed, both Broadwater Farm Estate and Grahame Park Estate are due to undergo such processes, which will likely displace some proportion of the working-class BME residents and pose challenges to the estates’ community organisations. Where in 1979, the Black community occupied the Metro Youth Club in order to resist its closure, today the Black community stays fighting to ensure the survival of spaces for Black youth projects. To this effect, the 4Front Project recently acquired a local building and transformed it into ‘Jahiem’s Justice Centre’ to expand their scope. On Instagram, they posted,

‘At a time where all resources have been stripped from Grahame Park Estate as a result of gentrification, we have reclaimed the old Chemist and transformed it into a powerful space for creativity, empowerment and healing – in the heart of our community.’

This is where we find hope, because this has not just been a tale of police racism, but a tale of community solidarity and racial resistance. Looking towards the future, it seems inevitable that the MPS will continue to identify Black youth projects as target locations, but if there’s one thing I’m sure of, it’s that the Black community will come together, resist, and fight harder to protect and create spaces for Black youth.

[1]Unless otherwise referenced, the cases mentioned below are from the IRR publication, Policing Against Black People (1987)

[2]Evidence from this paragraph pertaining to the categorisation of council estates and certain areas comes from Policing Against Black People (1987)

[3]In the case of the police raid on Broadwater Farm Youth Association in 1986, it is important to note that in Policing Against Black People (1987) it reads: ‘ostensibly to search for cannabis’