Tucked away in a quiet corner of Elephant & Castle lies 56A Infoshop.

Volunteer-run and 100% unfunded, it is a radical social centre, bookstore and archive.

What is a radical social centre? Social centres have many different influences. One is the long history of squatted buildings in England which opened themselves up as places for people to engage in radical ideas, activity and experiments. At its opening, 56A also drew inspiration from the Infoshop idea. Infoshops were numerous throughout many of Europe’s combative cities and provided space for meetings, the sale of books and papers, a site to gather and plot political actions, as well as the most simple idea – to be a place to find things out and what was happening!

As founding member C explained, “we called it an infoshop as a lot of us at the time were involved in the radical politics around creating a European network for distributing news about social struggles.”

“This was before the internet, you know.”

“Squatting is no longer a massive movement.”

Established in 1991 as an information hub for radicals, volunteer J described 56A as “a relic of the squatting scene in London.”

“Lots of the old squats that were really important have been shut down or developed out.”

“56A is the last man standing.”

Although now rent-paying, 56A was a squatted building from 1988 to 2003.

C believed that changes in the urban fabric were behind the movement’s decline, alongside the criminalisation of residential squatting in 2012.

“If you walk around the area today, you’d think it was just like any other part of London, but thirty years ago there were thousands of squats. The city is much more regulated and disciplined now, you don’t see that anymore.”

“Right now, everyone is struggling with awful conditions. Multiple jobs, low wages, terrible amounts of rent … it impacts how much time and energy we have to build spaces like 56A,” he added.

“We function because we trust each other.”

56A is collectively organised. Long-term volunteer D explained what this meant: “we operate without hierarchy. No one is in charge.”

“This creates many more possibilities for change and adaptability because things aren’t fixed.”

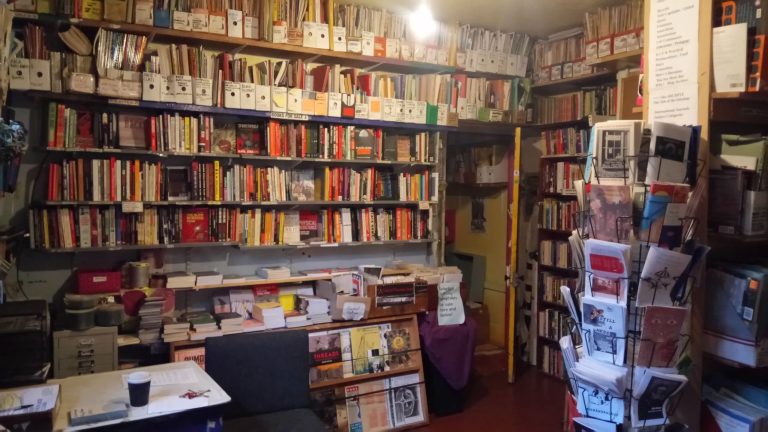

56A survives through the sale of books, zines and graphic novels. Or as Jess put it, “anything made out of paper.” The literature on offer tackles a range of topics from the Black Panthers to ecology – and everything in between.

J said: “we have a lot of rare items, books you wouldn’t find anywhere else.”

Prized by the volunteers was 56A’s open-access archive of over 1,400 books and 50,000 pamphlets, papers and leaflets.

“We are maintaining a history of past struggles and resistance,” said D. “Especially at a time when movements aren’t as strong as they once were, it is vital to keep a record of what people have done before.”

“There’s a lot of knowledge there that we shouldn’t forget,” she added.

“This is not a shop – it’s an experiment in community.”

More than simply a bookshop, 56A is a space where people can meet and be together.

“No-one is involved because they just want to sit and sell books”, explained C. “We are interested in the people coming in and what they are up to.”

“56A is like a living room. Some just pop in for a cup of tea. Others stay all day.”

Although an anarchist collective, he stressed that 56A was open to all. “This is not a place where you should feel that you are being sized up or worry that you might say the wrong thing.”

“Come. Be yourself.”

J described why such meeting points are valuable.

“In London, where there are fewer and fewer spaces that can be accessed without buying something, a place like 56A is really important because it is not determined by capital.”

“Communities need physical spaces where they can be together without having to spend money.”

“We are reaching a critical moment of unlivability in this city,” she continued.

“We are far from a revolutionary fossil.”

Yet there is a radicalism to 56A.

“If you were to summarise our politics it is anti-capitalist,” explained C.

“We are interested in alternatives to the current system. I know this is hard, almost impossible. But we are trying to give examples of possibility, to be an inspiration in some ways.”

He added: “You can’t do politics online. Movements run on two things. You need other people to do stuff with. You can’t do politics on your own. And you need spaces like 56A. It’s the infrastructure.”

In an ever-changing political context, the volunteers observed that 56A needed to be dynamic.

“We are constantly asking who are we, where do we come from politically, and what we want to do with the space,” said C.

“It is great to function as a repository of ideas,” he continued, “but if you come in and it is only stuffy old anarchist pamphlets that don’t mean anything to anyone it is pointless.”

“The amazing thing over the past years is how radical ideas are being re-invented, particularly by Black Lives Matter and anti-abolitionist movements, to critique power, oppression and the state.”

“We must ask if we are relevant to young people involved in these struggles.”

56A is politically active locally. Alongside mutual aid networks, union organising, prisoner solidarity and trans-queer activism, its members are involved in the ‘Up the Elephant’ anti-gentrification campaign and working against racist schooling.

“It is a fucking grim future, when you look at it macro-scopically,” said C. “But 56A must continue to exist.”

“We believe that, in its small way, this place can make a difference.”

“It provides hope,” added J.

J.W.E. Askew